The actual House of Windows as far as we could tell

Have you ever traveled in the footsteps of a book?

Visited the location where a character lived? Tried to retrace his or her steps? I’ve done this several times, such as on a trip to London when my kids and I visited where Hercule Poirot “lived” in the BBC series we love.

I got to do this again in Jerusalem a month ago, when my friend Rivka Levy took my husband and me around the neighborhood of Musrara, where she herself lived until recently. We weren’t following the footsteps of a character. Rather, we were hunting for the locations Adina Hoffman writes about in House of Windows. We believe the above photo shows the building where Adina Hoffman lived as she described it this way:

“With its flight of worn limestone steps, its slender columns and iron banisters, rising at intervals into delicate archways, the house called to mind a host of mismatched objects and structures, the entire assortment of which might suggest, together, something of its quirky elegance, but none of which alone does justice to the building’s eccentric proportions. It had the multiple, zigzagging decks of a luxury liner, the intricate balconies and catwalks of a stage set, the busy grid of a crossword puzzle, and the tall, spindly struts of an oversized canopy bed.”

“With its flight of worn limestone steps, its slender columns and iron banisters, rising at intervals into delicate archways, the house called to mind a host of mismatched objects and structures, the entire assortment of which might suggest, together, something of its quirky elegance, but none of which alone does justice to the building’s eccentric proportions. It had the multiple, zigzagging decks of a luxury liner, the intricate balconies and catwalks of a stage set, the busy grid of a crossword puzzle, and the tall, spindly struts of an oversized canopy bed.”

House of Windows, Portraits from a Jerusalem Neighborhood by Adina Hoffman, p. 1

House of Windows is a wonderful portrait of place, rendered, quite often, in exquisite lyrical prose.

I had given Rivka a copy of House of Windows. I figured she’d get a kick out of it, having fought her own battles trying to feel at home in Musrara. She wrote quite entertainingly about those in her Secret Diary of Jewish Housewife. Sure enough, she read House of Windows in one sitting and wrote about her impressions in Through Someone Else’s Window. Rivka brought her copy along on our jaunt. She showed us some of her spots, as well as some she thought were the locations of House of Windows, such as Ahmed’s Garden.

One of the old passageways in Musrara that I cannot find on a map. Rivka felt the garden on the right, where the palm leaves lean over the wall, must be “Ahmed’s Garden” from House of Windows.

“Ahmed brought something else to the garden, with his constant clearing, attending, adjusting, minding. I hesitate to name this thing, for I know that in its essence it has no satisfactory title, and that one walks a dangerous mine field of cliché when one mentions the simple happy native at work in the simple happy garden. But there is no getting around the fact that Ahmed, in his execution of these thousand tiny, spontaneous chores, had a weird, almost magical influence on the growth of the trees and flowers.”

House of Windows, p. 78

Ahmed’s Garden?

I was also curious about Musrara because it had been a divided neighborhood.

From 1949 – 1967 East Jerusalem was under Jordanian rule, and Jerusalem was a divided city just like Berlin had been. As I grew up in a divided country, namely the former West Germany, this strikes a special chord with me. I have jarring memories of the Berlin Wall from my first visit to Berlin in 1982. I have even more surreal memories of visiting East Berlin during that trip.

A divided city is a bizarre situation one doesn’t easily forget.

Streets dead-end in a wall, and dangerous no-man’s land abuts regular houses.

Jaffa Street dead-ended in the concrete border wall. This 1966 photo by Zev Radovan is now displayed on a plaque at this spot on Jaffa Street.

The same spot at Jaffa Street these days, looking the other way toward Tsahal Square. You can see the Old City walls and the Tower of David minaret in the background.

The operation to rescue false teeth accidentally dropped into this no-man’s land is one of those bizarre stories of divided Jerusalem:

“In 1954, a patient leaning out of the window of Jerusalem’s French Hospital sneezed, coughed or yawned so hard that her false teeth flew out of her mouth and landed on the ground outside. While today they would have ended up on bustling Paratroopers’ Way, at the time there was nothing here but a no-man’s land covered with twisted barbed wire, scorched armored vehicles, concrete barriers and land mines. To top it off, Jordanian snipers stood at the ready atop the Old City ramparts. Undaunted, one of the nuns from the hospital volunteered to retrieve the dentures. After painstaking preparation, and with the good will of Israel, Jordan and the United Nations, the chairman of the United Nation’s Mixed Armistice Committee held up a white flag and accompanied the nun into No-Man’s Land. Incredibly, the lost teeth were discovered among the weeds, refuse and barbed wires and returned to their owner.”

Former Israel/Jordanian Border No-Man’s Land, Jerusalem Post

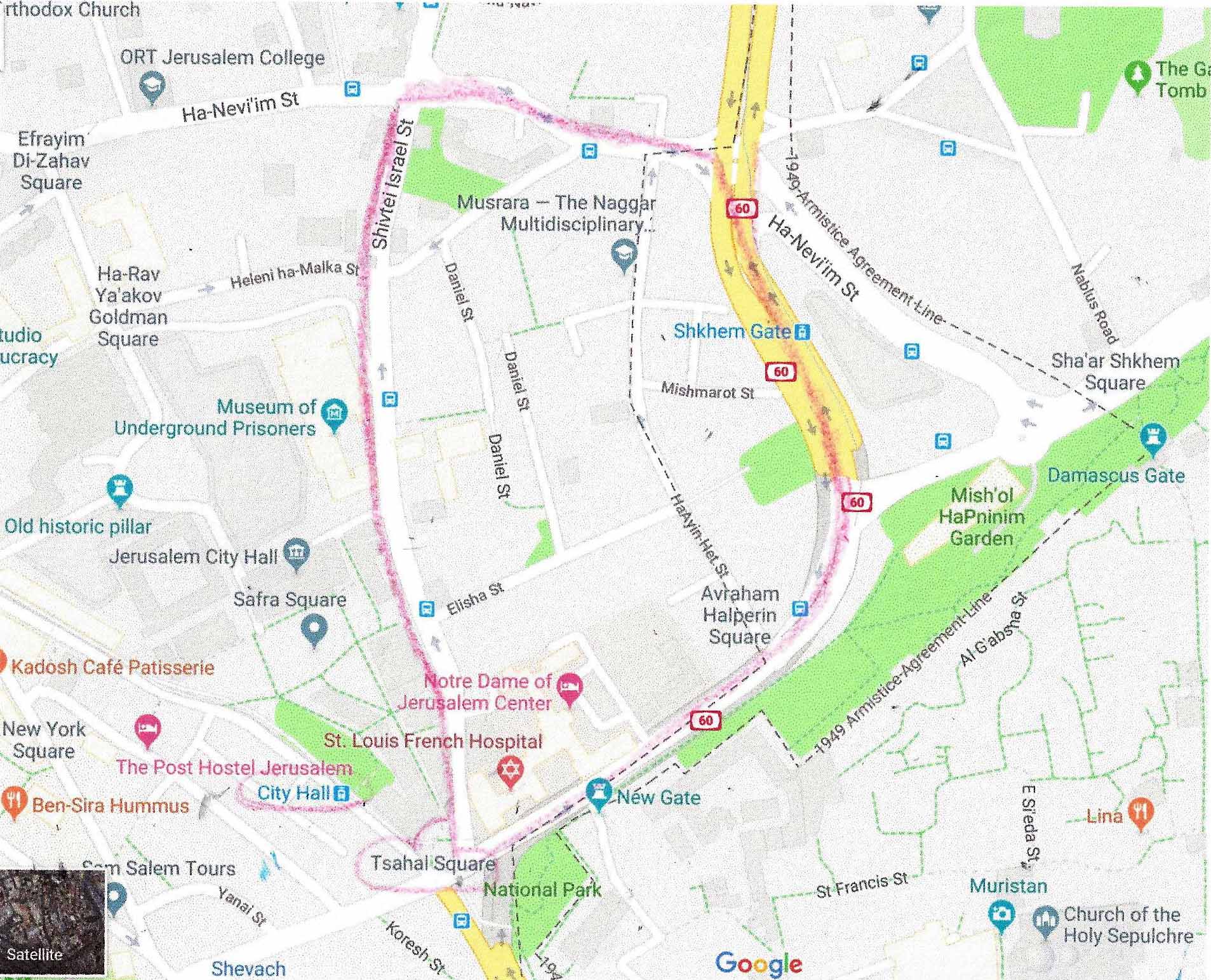

My scribbled-in pink line on this Google map outlines Musrara.

In the above map, the dotted line of the former border runs vertically through Musrara along HaAyin Street. To its right (east) was no-man’s land up to the armistice line of 1949.

HaAyin Street when we took our walk, looking south from HaNeve’im Street

Looking north into HaAyin Street at the corner of Elisha Street

These days, there’s nothing to be felt of this former no-man’s land, at least not in this area.

HaAyin Street is just a regular street and bears the signs of a growing city. Musrara, centrally located next to the Old City of Jerusalem, has become prime real estate.

Old house in Musrara with a new story on top

Rivka explained that most old homes in Jerusalem used to be one story, maximum two. These days, many property owners simply add another floor to their building, thus preserving the old while making more space. You can see this in the above picture. Once Rivka pointed this out, I noticed this all over the city!

An old and so far unrenovated house in Musrara

On the other hand, many properties are stuck in limbo. Property rights are unclear or disputed, sometimes an after-effect of the city’s erstwhile division. Some additions have been made without municipal approval. All of this can turn a property purchase into a nightmare, something my friend Rivka sadly experienced when she and her family tried to buy property in Musrara.

Public housing project in the middle of Musrara

Musrara is not all picturesque old buildings.

In its midst, it harbors this nasty sin of a building, erected to provide sorely needed housing back when Israel had to accommodate hundreds of thousands of Jewish refugees from Arab countries. But chances are, in a hot real estate market, an ugly apartment building like this one with fairly affordable housing is not going to last.

“I had passed these monolithic gray buildings every day since we moved to Musrara, though I’d ventured inside just once in all these years. The place was, in essence, the sum symbolic total of all the impassable-seeming ethnic and class barriers that still existed everywhere around us. Though our neighborhood was in theory fully integrated, it was in practice still divided, as newcomers like us had paid handsomely to settle in the elegant old Arab houses with their scalloped lintels, interior arches, and high, sometimes vaulted, ceilings. Meanwhile, the two urban fortresses at the neighborhood’s heart–boxy cement slabs constructed several decades before to provide the needy residents nothing more complicated than shelter–still belonged to the original occupants or their children and grandchildren, the only notable exception being a few slender-boned families of Ethiopians who’d moved in over the last decade. This was poor people’s housing, and though renovations had recently been carried out on the buildings’ facades–a decorative-stone false front stuck like a Band-Aid across the dirty concrete–there was no disguising the essential ugliness of the structures, or the basic character of the place as a home for those without the means to choose where they would live.”

House of Windows, p. 59

Ha-Nevi’im Street, Jerusalem

Bus stop on the corner of HaAyin and Ha-Nevi’im Street, Jerusalem

A walk that began retracing the footsteps of a book became another quintessential Jerusalem experience. In a small neighborhood like Musrara, one finds so much history, so much complexity, and yet also just everyday city life. Residents wait at a bus stop, go to work, run errands, look for parking. I, the visitor, of course take pictures. The above images I took in Musrara capture some of what I love about Jerusalem: its diversity of people, its contrasts, and always the old abutting the new.

Fascinating! Quite a story, and photos to match.

Thanks!

Beautiful post, thanks Annette. As you can see, you are also introducing me to new bits of Jerusalem that I never knew about before: https://rivkalevy.com/2019/02/10/the-limit/

Thanks for taking us around!