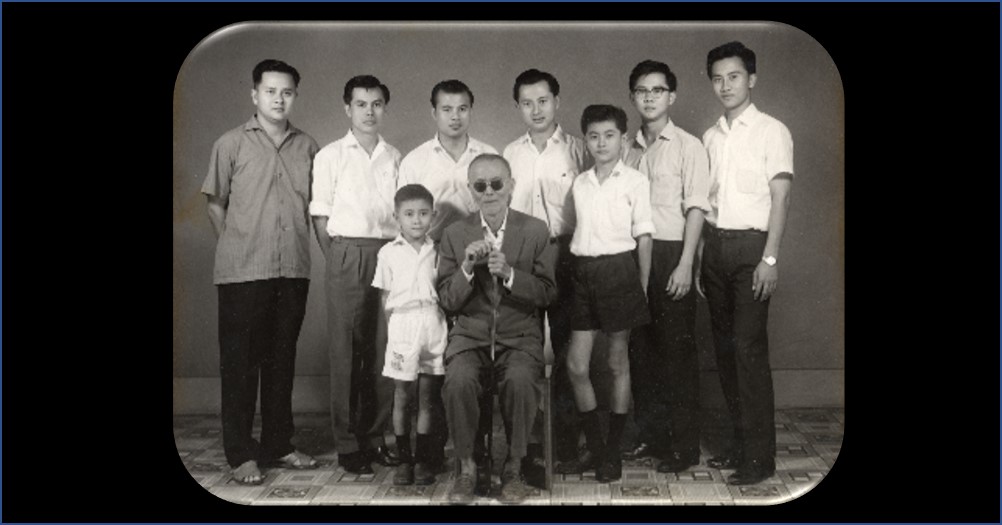

At my Great Aunt Resi’s for New Year’s Eve, early 1940s, Czechoslovakia (This picture is from my memoir Jumping Over Shadows.)

When you write a story from family history, the cast of characters can be quite large. This can be confusing to the reader.

So the issue of how to handle all those names within the text can be a challenge for writers of family memoirs.

First of all, you need to make sure your reader can easily follow the narrative.

It should always be clear who the characters are. Providing a family tree can be helpful, but having to refer to it often in order to follow the story can get cumbersome. If you ever read an epic Russian novel like Anna Karenina, you know what I mean.

I have found it is best to use proper names for main characters and to refrain from doing so with minor characters.

The goal is to avoid overloading the reader.

Not using names is easiest with relatives to whom you can simply refer by their relationship to you, the narrator, such as “my sister.”

This works well if the sister doesn’t appear often, as the reader immediately knows who she is in relation to the narrator. Since the narrator is the navigator of the story, this makes for good readability.

It also protects that relative’s privacy. Since you’re writing about real people, you have to deal with the additional issue of whether or not to use their real names. With this, there are no hard-and-fast rules but I feel that for minor characters it is not worth violating their privacy. In addition, if they are not identified by name, you don’t necessarily have to ask their permission before you publish. (With anyone you mention by name, it is best to make sure they are OK with your story.)

However, if the sister appears more often, referring to her as “my sister” can become annoying. In that case, using her name would be appropriate. If she prefers you don’t use her real name, use a fake one. She will still know who she is, but strangers won’t be able to Google her based on your story.

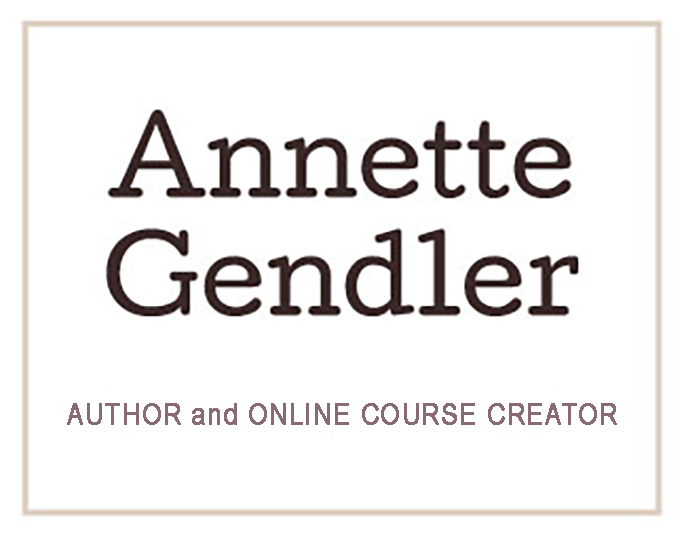

My friend Sherilynne’s grandfather with his sons, 1950s, Malaya (now Malaysia)

For other minor characters who are not relations, it is usually best to refer to them by the role they play in the story.

For example, refer to your “first-grade teacher” if that person only appears a few times. However, if a character appears more often, this becomes awkward. It can also give the impression that you’re hiding something. In that case, it is better to give that character a proper name and introduce him as “Mr. Frey, my first-grade teacher.”

The same should be done to reorient the reader if someone only appears sparingly throughout the text. So you could say “our housekeeper, Mrs. Burns,” when she shows up again, instead of expecting the reader to remember who Mrs. Burns was when she appeared ten chapters earlier.

Multiple people with the same name is often an issue in family stories.

If you are dealing with multiple “William Kellers” (an example from the American side of my family), providing middle initials, or “Jr.” doesn’t cut it. In an story you usually refer to main characters by first name, so you might have to resort to nicknames “Bill” or “Billy.” If that’s not acceptable, you could resort to “Uncle William” and “Cousin William”–some identifier that helps the reader keep them apart.

The fewer words you need to clearly name someone, the better.

For a main character, for example, “Billy” makes for an easier text to follow than “Brother Bill.”

Beta readers can be very helpful in giving you feedback when they got overloaded in keeping track of characters. As the writer, it is hard to tell which characters readers will remember and when they might get confused. Ask your beta readers to indicate where they would appreciate being reminded of who someone is.

Prompt: Write about how you got your name, whom you are named after (if you are), and why.

My book How to Write Compelling Stories from Family History is full of advice like this. For a list of 10 unusual prompts to get you started writing stories from family history, sign up for my newsletter.

Very helpful!

Thanks!

Good advice!