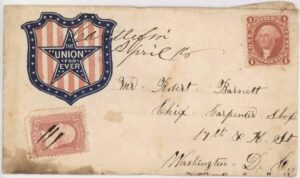

Civil War Letter (source: familytree.com)

When researching family history, you might come across a letter that you find utterly fascinating. But you don’t know much, if anything, about the person who wrote it.

This sends you on a quest to find out more about the letter writer. You do a search. You find out some stuff, but not much. But you’d still like to “do something with it.”

After my talk on writing stories from family history at the National Genealogical Society’s conference, an audience member approached me with just such a conundrum:

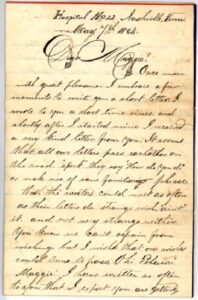

I found these Civil War letters. I don’t know who the letter writer was but reading these letters sparked my interest in the Civil War. It’s become a huge interest of mine, and I’d like to write about these letters. How do I do that?

First of all, this is the perfect setup for a personal story because finding these letters resulted in a change in this audience member.

First of all, this is the perfect setup for a personal story because finding these letters resulted in a change in this audience member.

It got her interested in the Civil War, igniting a new passion.

Change is a key ingredient of a story.

It provides the answer to the “So what?” question that you don’t want to hear from a reader.

Here’s what you do when you want to write about something, or someone, but have little material:

If you don’t have much information, you make your quest the story.

Quests are one of the classic hero journeys that make for a good story.

Just think of Treasure Island.

In this situation of not having enough information about the letter writer, you, i.e., the one who found the letter, will become the narrator and the hero of the story. Your quest to find out more, and your associated frustrations, dead ends, speculations, and discoveries will provide the story’s emotional energy.

This also gives the story a certain universality as readers will see themselves in this story.

Many people have gone on similar quests. They will relate to your search. Your trials and tribulations will resonate with them, and that makes for an engaging story.

Furthermore, a quest provides the action and forward movement a story requires.

A search is an inherent forward movement. The narrator wants something, and the reader is along for the ride, hoping the narrator will find it. Even if, in the end, the desired information is not found, we have enjoyed the ride. And, more importantly, like the narrator in this case, we might have found something we weren’t looking for: an insight, or as was the case with this audience member, a passion we did not have before.

One caveat: Don’t throw a lot of individual names at the reader.

Names are hard to keep track of and can quickly drown out the story itself. Genealogical searches often confront a reader with lots of names and family relationships that can quickly lead to mental overload for the reader. Finding Carla: How I Identified A Mystery Letter Writer was one such frustrating read for me. I thought it would be a fun mystery. Very quickly, however, I was overloaded in names I simply did not care about.

For a better way to handle this, see my post How Do you Deal with the Plethora of Names When Writing Stories from Family History?

There is obviously more to crafting a story based on a letter but a quest is a great place to start.

Interested in writing family history based on letters? Check out my upcoming online course:

Interested in writing family history based on letters? Check out my upcoming online course:

From Family Letter(s) to Fascinating Story

Begins July 10, 2022.

You might also be interested in:

How to Solve One of the Biggest Challenges When Writing Family History Based on Letters: Context

Good suggestions, Annette.

Thanks!