It is precious and rare to fall in love with a book. It is even more precious to get lost in a book and be swept away to another world.

It is precious and rare to fall in love with a book. It is even more precious to get lost in a book and be swept away to another world.

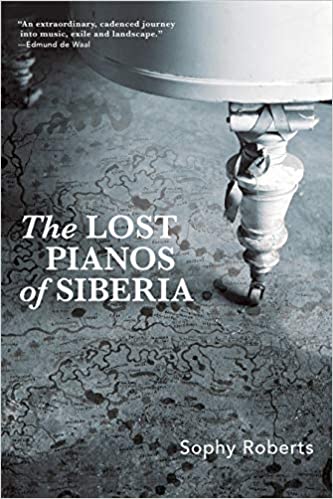

This just happened to me with Sophy Roberts’ wondrous The Lost Pianos of Siberia. I finished its 350 pages in three days. Then, hungry for more, I read its hefty source notes and historical chronology. Now I’m reading the articles on Roberts’ website.

br

What fun to have found a writer I can be a fan of! It’s been a long time since that happened to me. That’s also why I haven’t been sending out my reading list. I only ever recommend books I love. Hopefully this is the beginning of another happy reading streak.

br

Throughout this pandemic, I’ve wanted to get lost in a book. Yet I never had the brain space, the focus, or the leisure.

Then, last Saturday evening, I pulled my back out lifting our cooler. Stupid thing to do, I know! But I haven’t had back problems in years! When I felt that crack in my lower back, I knew I was in for a few days of immobility. Lying flat on my back, sometimes on a heating pad, is the best position for those upset muscles to heal. And that meant I could dive into The Lost Pianos of Siberia, which had just arrived.

br

Sophy Roberts had already captivated me with her article I was a Jaded World Traveler. Then I Went to Siberia in the Wall Street Journal’s July 18 weekend edition.

br

For some reason Siberia has always fascinated me.

I have an affinity for cold and desolate places rather than lush and tropical ones. Traveling the Transsiberian Railroad from St. Petersburg to Vladivostok is one of my lifetime travel dreams. Last year I tried to persuade my daughter to take that trip with me as we were looking for a destination for her college graduation trip. It was the rare summer when she would have had a month to travel, and that train ride takes three weeks if you want to explore places along the way. However, I didn’t convince her. We ended up traveling to Peru. Not that I’m complaining…

br

Sophy Roberts’ article in the WSJ stuck in my mind. I noticed that her book, The Lost Pianos of Siberia was about to be published. Then came a glowing review of the book in the WSJ, which is not easy to please. I immediately ordered the book, hoping I would finally actually read a book again. Mind you, other book purchases, based on great reviews, are still lingering in my TBR pile.

br

Then my back injury happened, and I got to travel to Siberia in the second-best way possible: Whisked away by a book.

Or maybe this is even the best way to travel? Considering all the possible discomforts and annoyances of travel? Cold, heat, bugs, delays, illnesses? I learned, by the way, that Roberts traveled to Siberia mainly in the winter. Turns out that summer is not the best time due to the tundra’s ferocious mosquitoes. Perhaps my daughter’s lack of enthusiasm spared me an ordeal last year?

br

These days, during the Coronavirus pandemic, traveling by book is certainly the best, and maybe even the only way to travel.

The Lost Pianos of Siberia is, however, way more than a travelogue. I love history, travel and personal, family stories, and this book has all that.

First of all, it is a work of art. Each chapter begins with a map of Siberia, customized to the relevant locations. I leafed back to those maps quite often. Despite the vastness of Siberia, I always found myself comfortably oriented.

br

The book is also thoroughly annotated. You always know where Roberts’ anecdotes, stories and quotes come from. Yet it never feels academic.

br

With a light touch, Roberts sketches in Russia’s turbulent history as well as Siberia’s cruel one. She elegantly educates the reader about the history of the piano and how it gained popularity in Russia. The piano’s many Russian (and foreign) virtuosos make appearances. Often, their fates provide the hook for a particular Siberian location’s portrayal. The artificial Soviet city of Akademgorodok, for example, becomes the story of the pianist Vera Lotar-Shevchenko.

br

And that’s what the book is ultimately about: The hunt for stories.

There is the search for pianos, a quixotic premise to be sure. And while that search provides Ms. Roberts with a purpose and a frame for her forays into the far-flung corners of the Russian hinterland, she’s also wise to what’s happening to her. She sees a bit of herself in Kate Marsden, whose book about traveling to Yakutsk in 1890 to find a Siberian herb that might cure leprosy, she “adores.” Roberts says:

br

“the more this English nurse was taken in by Siberia, the more she lost sight of the object she had come to find.” (p. 312)

Siberia, in all its facets, takes center stage. I tend to associate Siberia with endless snow plains, and Ms. Roberts’ descriptions of the Yamal Peninsula, for example, certainly fit that picture.

br

Lake Baikal by Daniel Born via unsplash

I did not realize, on the other hand, that a place like the Kamchatka Peninsula is stunningly beautiful.

“Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky, or Petropavlovsk for short, is unlike any other Russian city. At night, there is something of San Francisco to the pinpricks of light curled around the hills, dips and shoreline.” (p. 292)

br

Descriptions like that had me looking for images of that location. And so I learned that behind Kamchatka’s main city of Petropavlovsk, crowded with drab Soviet housing blocks, rise volcanos, much like Mount Rainier looms over Seattle. Roberts’ rendering of Kamchatka, reachable only by boat, reminded me of what I had seen on a trip to Alaska, its counterpart on the other side of the Pacific.

br

Petropavlovsk-Kamchatka, Photo by Sasha Panarin on Unsplash

Ms. Roberts’ depiction of Harbin in Northern China resonated with what I had read in Secrets and Spies – The Harbin Files. This book was my favorite read of 2012. It is an impressive memoir of another woman’s relentless quest, in this case to find out what had happened to her Jewish ancestors after they left Harbin for the Soviet Union. Roberts’ narrative echoes that story. She also picks up the thread of the tragedy of Harbin’s wealthy and successful Kaspe Family, which I first read about in Dara Horn’s marvelous article on Harbin’s Jewish history: Cities of Ice.

br

This is the best kind of reading: When bits and pieces in various books you have read connect.

From The Harbin Files, I already knew about the freezing forced labor camps of Kolyma. Moustafine followed her great-uncle’s trace there, traveling to a forlorn snowy memorial of one of the mass graves to pay homage. Those passages were hard to read.

br

Miraculously, despite the sinister history of so many of the places Ms. Roberts visits, not one passage was hard to stomach.

They are sad and poignant, but not grueling. That, I feel, is the right way to honor the dead: Telling their stories, their terrible fates, so we get to know them.

br

The Lost Pianos of Siberia is not without faults, of course. Any good work of art, and anything you fall in love with, needs to be, I would argue.

Why would someone, who is not a musician, get so obsessed with pianos? Why travel thousands and thousands of miles in forbidding territory to hunt for a historic piano for her Mongolian pianist friend? An object that would require expensive restoration and even more expensive transport? I remained unconvinced, and that setup struck me as a thinly veiled excuse for all that adventurous travel. After all, Roberts specializes in remote travel.

br

The quest for pianos in places like the Kuril Islands, where there’s hardly a human dwelling these days, struck me as not only quixotic, but frivolous.

Whenever Roberts traveled to the most far-flung places, it was clear to me that there wouldn’t be a piano to be found. And I kept wondering who financed all these cumbersome trips, interpreters, researchers, transporters, etc.? And even if a piano were found, how would she transport it from, say, Sachalin to Mongolia? Who would finance that?

br

I happen to know that moving a piano is a huge feat: My mother owns a baby grand. When she moved to a senior citizens apartment a few years ago, my siblings and I chipped in to have it moved. That two-hour drive cost more than a thousand euros.

br

At times I also wished I would have been more in on Roberts’ journey. I wanted to hear about her travel experiences, be clued in on the fears, annoyances, joys and frustrations. Thankfully, the book’s accompanying website shows a fabulous movie of rides on various outlandish vehicles. I just wish the book had shared more of the rides, the food, the weather, the sounds and smells.

br

Nevertheless, The Lost Pianos of Siberia gave me what only the best books will give: Days of pleasurable reading and a journey to another world and another time that expanded my horizon.

Excellent review!!

Thanks!

Definitely sounds like a book that I want to read. Thanks for the recommendation.

I think you’ll love it!