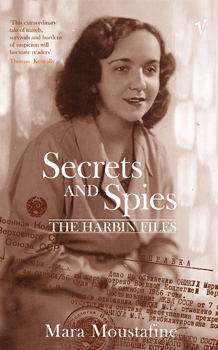

Of all the books I read this year, the one I have thought most about, talked most about and continue to think about is Mara Moustafine’s Secrets and Spies – The Harbin Files.

Of all the books I read this year, the one I have thought most about, talked most about and continue to think about is Mara Moustafine’s Secrets and Spies – The Harbin Files.

Unfortunately, the book is hard to get in the U.S. as it was published in Australia in 2002. My friend in Shanghai gave it to me when I was visiting because of my interest in the Jewish history in China. (My number one wish visiting Shanghai, except for strolling the Bund, was to visit the former Jewish ghetto area.)

I started reading Secrets and Spies on the flight back to Chicago, and I was plunged into a vanished world that still echoes in my thoughts.

Moustafine was born in Harbin in Manchuria, in what used to be Russian China. Her immediate family emigrated to Australia in the 1950s, once Mao’s regime did not tolerate “foreigners” anymore. Her great-grandparents had left Harbin for the Soviet Union in the 1930s, only to be either executed in one of Stalin’s purges, or sentenced to a forced labor camp.

In the 1990s Moustafine travels back to Russia and China to trace the stories of those lost relatives.

She digs through KGB archives to piece together what happened to these relatives. The book’s cover shows her great-aunt Manya, executed in Gorky in 1937 for “spying” for the Chinese. Her only crime, in turns out, was her family background, namely coming from Russian China, and being Jewish.

From reading Secrets and Spies, I feel I understand a bit of the Soviet Union’s terrible history, and a bit about the history of northern China. To me that is one of the powers of memoir: It gives the reader a “report from the front,” a personal insight into history.

This book fascinated me particularly because as a memoir writer I concern myself with the family history of vanished cultures. Moustafine comes from, and went back to, a land that is no more: Russian China, and Jewish life in Russian China.

I found her unrelenting quest to find the files that would disclose what had happened to her great-grandfather, her great-aunt, and her great-uncle, and all the others immensely admirable. At times it was hard to read about the terrible fates they suffered. Nevertheless the narrator swept me along on her search.

All the while I was asking myself: Where does this drive come from? Why is it so important to figure out what happened in the past? Why was she willing to travel thousands of miles, and deal with all kinds of bureaucracies, only to find out where and how someone like her great-uncle was murdered?

In part I was asking myself this because I saw my own quest mirrored in Moustafine’s. I also went “back” to my grandparents’ hometown of Reichenberg, now called Liberec, in the Czech Republic, in 2002. I wanted to see their house (which is still standing), to walk their streets, and sit in their café (which was still open then). Since then I have been back twice and have perused the archives in Liberec. For the memoir I am writing about that family history, I wanted to know what it was like to live there in 1938 when Hitler annexed the so-called Sudetenland. My grandparents were well known Social Democrats. Thus they were on the wrong side of the fence when the Nazi frenzy took over their city. Like Moustafine, who was reading through Russian files, I was reading newspaper archives in another language. In my case they were printed in old German script, which thankfully I can read.

I can say for myself that going back and piecing together the past did help me understand what was lost. And why is that important? Because, at least in my case, what was lost has resonated in my life.

After being expelled from Reichenberg after World War II, my grandparents brought their culture to West Germany, where I grew up. My father’s loss of a homeland as a 13-year-old boy put him on the trajectory of venturing out to live in an entirely different culture, namely the U.S. and marrying an American. The next generation, namely my siblings and I, grew up with a sense of being in between cultures, and, at least in my case, never quite at home in Germany.

I even wrote to Mara Moustafine to ask her what made her embark on her quest. Writing a letter to an author whose book got me thinking is something I always mean to do. But I hadn’t done that until now!

I love that you contacted the author! That's a turn I didn't see coming from that prompt, and I love to be surprised, so this makes my day!! 🙂 Thank you so much for sharing! 🙂

rebecca – I didn't see that coming, either, but once I was writing about this book, I felt I had better let the author know.

It sounds compelling!

I'll have to track it down….

William – it is definitely a compelling book.