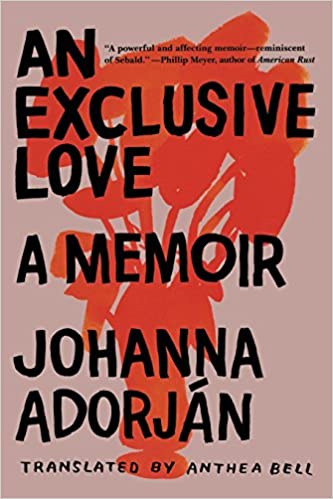

On the surface, Johanna Adorján’s An Exclusive Love is about her grandparents’ suicide. But it is really a love story, in more way than one, with all the requisite tragedy. And to any student and lover of memoir, it is an interesting study.

is about her grandparents’ suicide. But it is really a love story, in more way than one, with all the requisite tragedy. And to any student and lover of memoir, it is an interesting study.

Adorján’s handling of time is deft.

She imagines her grandparents’ last day and uses it as the frame for the book, embedding in it their story as Hungarian Jews who survived the Holocaust and later relocated to Denmark after the failed Hungarian anti-Communist revolution of 1956. She also folds in her reminiscences of this glamorous pair as her grandparents.

The depiction of their last day becomes increasingly poignant, as the reader is aware that the grandparents do all those mundane things – fixing coffee for breakfast, listening to classical music – for the last time.

Invariably, we are engaged in the story simply because we start imagining what we would be doing on our last day.

Would we be testy, or would everything suddenly be more important? Would we go about it as business-like as Adorján imagines her grandparents did? Some squabbling, but no references to “this is our last chance.” I was gulping back tears when they drop their dog off with a neighbor under the pretense that they are going on a vacation to Munich to visit their son. Adorján even dares to intersect both timelines, hers and that of her grandparents, when she calls them two days later, the phone ringing through the empty house where their bodies still lie undiscovered.

Adorjan only subtly faults her grandparents’ for deciding not to continue on, not to live for their family.

This applies especially to the grandmother, who was healthy and clearly decided that she did not want to go on living without her husband, who was older than her and obviously deteriorating. Her suicide carries the message that the rest of the family, son and daughter and their families, were not important enough for her to live for them. Having to live with that implied rejection is certainly part of why Adorjan set out to learn who her grandparents really were, apart from being her grandparents.

She openly shares her research, her visits to her grandparents’ friends in her quest to learn more about them.

After all, they killed themselves when the author was twenty, i.e. not at an age at which one necessarily has gone about asking the older generation about their lives. In the end, she finds out very little that she did not already know because her grandparents were an “exclusive” couple. Close to each other and very rarely close to anyone else. The word “exclusive” means so much here – something exquisite that the grandparents were fortunate to have, something others admired (more than once, the couple is referred to by friends and relatives as “glamorous” and “beautiful”), but something that also excluded those who might have been close to them.

The book is also a tribute to another generation that perhaps did not put too much weight on self-examination but rather on putting the past behind them to focus on living the good life.

In one instance, a friend of the grandmother remarks that she cannot understand why nowadays people make a big deal out of rape. She was raped by Russian soldiers who were “careful” as she was pregnant at the time. It happened to everybody, OK, so you take the hit and move on. That seems to have been the attitude of that generation. I was left wondering: Clearly these people survived horrific traumas. Nevertheless, they moved on to live successful and sometimes happy lives. Who is to say theirs is not the right approach?

More than once Adorján mentions that her grandparents, especially her grandmother, implied that she wouldn’t have anybody else decide when she would die. She would decide that.

Coming from a Holocaust survivor, I could somewhat understand that choosing their own death, when and how to die, was in a way an ultimate triumph. However, I must say that all the Holocaust survivors I have known were quite the opposite: fierce lovers of life.

An Exclusive Love also had me wondering whether in the U.S. we take the genre of memoir a little too seriously.

Adorján remarks as much in her interview with SMITH Magazine. One of my students, representative apparently for many U.S. readers, had an issue with Adorján’s reimagining her grandparents’ last day because this account is obviously fictionalized. No matter how much of it is based on research (She does, chillingly, quote the police report at the end of the book.) and her knowledge of her grandparents’ usual way of operating, the reader knows that the narrator was not there.

I read the book in the original German, and I noticed that its cover does not have any reference to “memoir” or nonfiction.

I went to my bookshelf to look at other books I’ve read in German that we would classify as memoir in the U.S., for example, Ruth Klüger’s weiter leben , or Lenka Reinerova’s Mandelduft

, or Lenka Reinerova’s Mandelduft . If anything, they say “Erzählungen” on the cover, which means nothing more than “tales” or “stories.”

. If anything, they say “Erzählungen” on the cover, which means nothing more than “tales” or “stories.”

There is no mention of memoir or nonfiction. The authors tell their stories and because they didn’t imagine the whole thing, the cover doesn’t say “a novel” or “short stories,” they are simply stories. Like the stories we tell around the kitchen table. Stories of their lives, of our lives, as they remembered them, heard about them, and maybe imagined them. It could be as simple as that.

Sounds like strong stuff in the book you wrote about today. Certainly thought-provoking. I found it most interetesing that the German books you mention have nothing saying it is a memoir or nonfiction. Is the attitufe :Let the reader discover it herself' or is it that we here have raised memoir to greater importance? Could be a lively discussion on that question.

http://www.writergrannysworld.blogspot.com

This sounds amazing. Thanks for sharing. I need to add it to my ever-growing must-read list.

You had me in tears just reading your review- you wrote it so beautifully! Now it makes me want to get my hands on the book. You touched on some interesting things- which I have discussed extensively recently with friends- this idea of not looking to what happened in the past- but looking forward to living the good life. Too much introspection- and analysis may not be such a good thing.

Great review!

Yep, I'm adding to my "must-read" list/ pile too. Thanks for sharing. I'm new to your blog and greatly enjoying perusing it.

Nancy – indeed this is good fodder for discussion. In the German books it's clear, at least it was to me, that you're reading nonfiction, even without the label. To me, the key is that if you as the reader know which parts are imagined, then that's OK, even if the overall book is nonfiction.

Tia – it's a stunning book and a relatively short read, so I hope you get around to it!

Anjuli – good to have you back, I've been missing your comments! Yes, the point about moving forward in life is worthwhile contemplating although I must say I like rummaging in the past.

Teresa – welcome to my blog! If you do read An Exclusive Love, I'd like to hear what you thought.

It's an interesting thought that the book was not labeled as memoir or nonfiction, especially as I struggle with putting my own story on paper. I'm finding that the only way I can get the story down is by taking freedom with the form. You're right that it's important that the readers are clear when a writer is taking liberties. I think that's where some of these memoir "scandals" began.

Julie – that's exactly where the memoir scandals come from: selling something as "this really happened" when it didn't, or you're not sure. As long as the reader knows what you're up to, you're fine. Some people don't like fictionalization in memoir but at least you're not deceiving them if you're open about it. The deceit is what breeds the resentment.