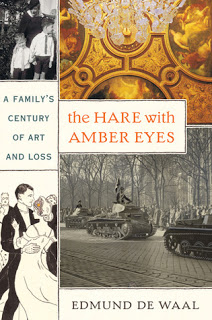

Edmund de Waals’ memoir The Hare with Amber Eyes was my favorite memoir of 2011. I am still trying to figure out why because it defies so many of the principles of good storytelling.

There is very little scene, as the book is almost entirely told in summary. Sometimes the descriptions get pedantic, and few of the characters are fully developed.

Nevertheless, I found this family saga captivating.

The narrator’s quest to figure out where the Japanese netsuke figurines he inherited came from becomes the story. Quite often, however, I forgot about him and the netsuke. I got into the lives of the ancestors he was investigating, this Jewish family originally from Odessa, who built up a bank and so desperately tried to be accepted into society.

By always returning to the netsuke, De Waal manages to hold together a saga that sweeps across centuries and countries.

He conjures fin-de-siècle Paris, Vienna from before World War I all the way to 1945, and then moves on to a devastated post-war Japan, with brief stops in present day Odessa and the author’s home in London.

The book fascinated me because I have gone on a similar quest myself, reconstructing the lives of my grandparents, great-aunt and great-uncle in 1930s and 1940s Czechoslovakia. So of course I am going to be interested in a story like this, and yet I have read many equally promising ones that bored me.

Perhaps the magic of this book lies in the powerful poignancy of certain episodes, certain junctures in these people’s lives that de Waal tells masterfully and that made me disregard the book’s other possible shortcomings.

Never before, for instance, have I read such an utterly devastating rendering of what it must have felt like to have one’s life taken away in Vienna in 1938, simply because one was a Jew, even if a wealthy and supposedly well respected one like his great-grandfather Viktor.

This passage is from chapter 26, right after Viktor’s bank has been “Aryanised.” He and his wife moved to servants’ quarters in their very own palais on Vienna’s parade street Ringstrasse:

“Viktor goes down the unaccustomed steps to the courtyard, passes the statue of Apollo, avoids the looks of the new officials, and the looks of his old tenants, out of the gateway, past the SA guard on duty, onto the Ring. And where can he go?

He cannot go to his café, to his office, to his club, to his cousins. He has no café, no office, no club, no cousins. He cannot sit on a public bench any more: the benches in the park outside the Votivkirche have Juden verboten [Jews prohibited] stenciled on them. He cannot go into the Sacher, he cannot go into the Café Griensteidl, he cannot go into the Central, or the Prater, or to his bookshop, cannot go to the barber, cannot walk through the park. He cannot go on a tram: Jews and those who look Jewish have been thrown off. He cannot go to the cinema. And he cannot go to the Opera. Even if he could, he would not hear music written by Jews, played by Jews or sung by Jews. No Mahler and no Mendelssohn. Opera has been Aryanised. There are SA men stationed at the end of the tram line at Neuwaldegg to prevent Jews from strolling in the Vienna Woods.

Where can he go?”

I must say I am eagerly awaiting de Waal’s next book, which is supposed to be called “The Story of White” and will tell the story of porcelain. Never mind that the man is first and foremost a world renown ceramicist, he can tell stories.

oh my- that excerpt is amazing!!! It really makes me want to read the entire book.

Odessa is a pearl of Ukraine and the Black Sea and lots of tourists visit this wonderful city every year. To feel an atmosphere of Odessa, visit its cozy cafes and talk to local people. Ukraine Travel Guide created a directory of the best Odessa cafes to help tourists. You may also find there tips on accommodation, car rent, theatre guide and much more. Actually, you will find there everything you may need for Ukraine tourism.