As announced last Monday, I am happy to welcome Shirley Hershey Showalter as a guest blogger today. We met in the online world last year; I was initially intrigued by her 100 Memoirs blog in which she set out to read as many memoirs as possible to learn how to write her own. I left comments, and we connected. I have followed Shirley’s quest to write her memoir about growing up Mennonite, and I was particularly curious how she tackled the dicey topic of writing about faith, mainly because I have been struggling with how to do that myself. So I am thrilled that Shirley was willing to share her insights (Thank you, Shirley!):

As announced last Monday, I am happy to welcome Shirley Hershey Showalter as a guest blogger today. We met in the online world last year; I was initially intrigued by her 100 Memoirs blog in which she set out to read as many memoirs as possible to learn how to write her own. I left comments, and we connected. I have followed Shirley’s quest to write her memoir about growing up Mennonite, and I was particularly curious how she tackled the dicey topic of writing about faith, mainly because I have been struggling with how to do that myself. So I am thrilled that Shirley was willing to share her insights (Thank you, Shirley!):

Writing About Faith – Imagine a Plane Ride

by Shirley Hershey Showalter

We all know that politics and religion are like the third rail of conversation. But do they have to be?

If you and I meet on a plane or train and fall into conversation, it’s only a matter of time before something one of us says leads me to tell you I’m Mennonite. Here’s how you might find out:

“Where did you go to college?” Eastern Mennonite University

“You were a college president? Where?” Goshen College, a liberal arts and Mennonite college in Indiana

From there, you either drop your questions and turn to your Coke and peanuts, or you push on:

“Did you drive a horse and buggy instead of a car?”

“No. You are thinking of the Amish, who are ‘cousins’ to the Mennonites but practice a stricter separation from the world.”

“Is it true Mennonites are pacifists? Why?”

“The Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5) is the centerpiece of the Bible from a Mennonite perspective. Many generations of Mennonite teaching and community life go back to the belief that Jesus meant what he said there, including ‘Love your enemies.’ ”

“You don’t look like a Mennonite.”

“I was a ‘plain’ Mennonite in the 1960s until my branch of the Mennonite Church no longer required prayer coverings and plain dress. I hope I’ve moved from being ‘plain’ externally to being ‘simple’ internally. I still feel respect and kinship for the best of the more conservative Anabaptist (both Mennonite and Amish) traditions.”

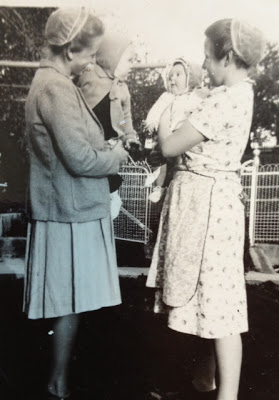

|

| My 21-year-old mother holds me on the right. My aunt holds my cousin on the left. Date: early fall, 1948 |

I’ve enjoyed many conversations with strangers over the years. The best ones of these turned into mutual exchanges. I might ask, for example, the question Krista Tippett often uses at the beginning of her radio show OnBeing: “What was your religious or moral environment as you were growing up?”

This way, I’ve heard quite a few faith stories from other people of many religions and no religion. In general, when people share their experiences of faith descriptively, others find them interesting. Being different from the mainstream actually makes your story more interesting. It took me a while to figure that out.

For a long time, I was embarrassed about wearing a prayer covering in public school and sitting on the bleachers as the other kids learned to dance in gym class. Now those stories are at the very heart of the memoir I’m writing called Blush: A Mennonite Girl in a Glittering World. I’m currently revising the manuscript and expecting publication in the fall with Herald Press.

So if we can have heart-felt and mutual conversations about religion with strangers in person, how do we translate that experience into writing memoir?

Here’s my thesis:

Writing about religion is a lot like talking to a stranger on a plane.

If the subject comes up there naturally, it might be one to consider for your writing. If it doesn’t, perhaps your story should focus on other aspects of your life.

My advice:

Be transparent.

Tell the truth about your religion, both the good and the bad.

No religion is perfect. All religions have made a contribution to individual

lives and cultures.

Write from your heart.

Focus on experience rather than doctrine, unless and until the doctrine impacts your own story. Then feel free to share how you were moved, drawn in, transformed, defeated, terrified, shamed, or otherwise impacted by your faith.

Invite rather than exclude the reader.

If you have followed the first two pieces of advice, you will have created a space wide enough for both you, the protagonist of your story, and the reader. The reader is on your side, wondering what will happen to you as you navigate the differences between your internal desires and the external realities of your life.

Readers may even start pondering their own values, beliefs, and commitments. This would be wonderful! But they will close the book if they sense you have the hidden motive to convert them. On the other hand, if you do this well, you could be the member of any religion and a sympathetic reader could be someone of a religion in conflict with yours. Does this happen often? No. Would it help us to live more peacefully if it did? Yes.

Do you talk about your faith or your religious background to strangers? Does this analogy make sense to you, or do you think it better not to get into this subject?

Wonderful post, Shirley, and thank you for sharing, Annette!

I talk about my current faith more than my religious background because my background is so fraught with doubt, fear and guilt. It's not something that I can easily discuss in a conversation with someone I don't know well. I am more successful writing about it.

Tina Fariss Barbour – thanks for stopping by. It's interesting, isn't it, that sometimes it's easier to write about something than to talk about it.

Yes, Tina, two good points here. Sometimes the religion of childhood is not easy to talk about. As an adult, we get to choose (usually) and therefore (usually) don't have as many issues around power and freedom in a belief system we ourselves chose. In childhood we are affected by the religion (or no religion) of our parents, for good or ill.

Also, writing is almost always easier (at least for introverts) than talking, partly because you don't have to worry about an audience until you choose to share the writing.

Choice, in both cases, matters.

Shirley,

Also, your reading audience doesn't argue back when you are trying to get your point across. Depending on what you have to say and how the readers feels about it, you may encounter them at some point. I often wonder if that will happen in my story about an American girl who goes to El Salvador during the civil war, not because of the religious implications, but because of the political implications.

Dear Annette and Shirley, This post has great meaning to me as I struggle to weave in my own faith into my memoir. Faith and religion are such sensitive and deeply personal topics and yet they are a big part of people's lives. My biggest fear is that I will alienate readers by sounding like I am preaching or trying to convert them to my way of thinking and believing. Rather my intention is to share my life story through the lens of my faith and upbringing as a Roman Catholic and hope the reader will tap into their our source of spirituality, whatever their religious denomination is. Your analogy of sharing with someone on a plane is brilliant. Thank you both for addressing this topic and for providing such clear direction. Shirley, I eagerly await your memoir!

Kathleen – thanks for your comment, glad to hear you found Shirley's take on writing about faith helpful. The key to not being preachy, it seems, lies in keeping it personal.

Well said, Annette. And Kathy, you have such a compassionate, open, curious spirit. It comes across even on FB and Twitter. Your voice, especially your tone, will keep a lot of readers with you even if they have issues with your religion. It might help to read memoirs like Mary Karr's Lit, Rhoda Janzen's two books (especially Does This Church Make Me Look Fat), various books by "Mormon girls," and, of course, classics like Thomas Merton's Seven Storey Mountain or Dorothy Day's The Long Loneliness. Anne Lammott's work is a lovely example, too. Her latest is about prayer.

Perfect advice, Shirley.

I like your sparkly new title.

Thanks, Shirley!

I appreciate your thoughtful feedback and recommendations, Annette and Shirley. I like the idea of speaking from my heart and keeping it personal and will keep this in mind as I continue along. Thank you both!

Excellent post. Chicken Soup for the Soul has a new book out titled 'finding my faith' The book is filled with stories about people who found a lost faith, found it for the first time and more. I suspect for many that it was easier to write about it than to talk about it to an individual. I have a story in the book (The Body Beautiful) which is about an experience I had at a church camp as a young teen. I don't believe I've ever told anyone about it until I wrote the story. Thanks for an enlightening post.

Nancy – congrats! It still amazes me how you always nail it with one of those Chicken Soup topics. Good point, too, that sometimes it's easier to write about something rather than talk about it, which I think is one of the great powers of writing. It gives us another way to open up.

Thanks, Nancy,for telling us about a great new resource, filled with many approaches to writing about faith. I love the title of your story and would be very intrigued if I were scanning the Table of Contents. You make a good point about speaking v. writing. I guess I chose the speaking analogy because I get asked about being Mennonite by strangers. That would probably be less true if my denomination were more mainstream, say, Methodist. People would assume they knew more about it.

Shirley: I appreciate your comments about struggling with how to talk about your faith in both personal encounters and in writing. My own experience is that it is much easier to do so in writing than in person. Earlier this year I published my boyhood memoir called The Flying Farm Boy: A Michigan Memoir. It includes stories about family and school and farming as well as about faith. I tried to present my joys and struggles about my faith in just as open a way as all my other stories. In this way I hope people who don't share my religious background(Dutch Reformed) will still be open to reading the book. Having a broader focus will hopefully open the book up to more people. So I guess my point is that we need to share other parts of our lives with people if we expect them to be interested in our religious beliefs, too.

Daniel Boerman – thanks for your comment. What you're saying applies to any memoir: the narrator needs to be fully fleshed out in order for the reader to go along, but when that happens, we are likely to go along on just about any topic. I've read two baseball memoirs now and I am totally not interested in that sport, but I was interested in the human quest that was so well done in both these books.

Hi Daniel,

I love the idea of a flying farmer, and I am going to have to look you up. Having lived in Kalamazoo, MI, for six years, I have a number of good friends from your tradition.

And I think you make a great point. Sometimes we need to connect first on other subjects. All listening is based on trust, and to listen about someone else's religion may first require establishing trust in other areas.

I love Blush: A Mennonite Girl in a Glittering World–what a great title! I think most people are interested in religion and faith. The most intolerant of it are militant unbelievers, who usually seem pitifully ignorant, though some are in my family and I love them.

Richard Gilbert – thanks for stopping by. Militancy doesn't really have a place in any kind of good writing, right? So I think you are right in that many people are indeed interested in religion and faith, and want to learn about how other religions operate, and a memoir is a beautiful window into that private world.

Thanks, Richard, for loving the title. Now all I have to do in revision is live up to that promise. Eek!

And thanks for loving those militant unbelievers. "My religion is kindness," says the Dalai Lama. Hard to argue with someone like that. I distrust unkind voices whether they are religious or not. But I'm also called to love regardless. Thanks for reminding me.

It makes sense to me, Shirley. Good post!

I don't quite use faith per se in my manuscript… more like a reaction against it as an underlying theme. Unkind voices, as you say, play a part in setting things in motion.

Shirley, your guidelines certainly slice through the confusion. You make it sound simple and doable to write about faith. I don't know if it's easier to write about it than talk about it. That may be the case for someone who is clear about their beliefs, but when more reflection is needed, tongues may freeze and writing go in circles. That reflective element may be a step or two before your advice comes into play, but on the other hand, your list could be used as a great set of prompts for managing that reflective process. Obviously, I found this a thought-provoking post. Thank you Shirley for writing it, and Annette for hosting Shirley.

Sharon – excellent point: You probably do have to be clear about your faith in order to talk and write about it, although I'd venture to say that writing about it might help a little with gaining insight.

What an excellent post! Being an avid memoir reader- I quickly warmed up to this post. I too look forward to Shirley's memoir. Thanks Annette for hosting this piece!

As far as the question at the end of the post- I cannot slice between my belief and myself- they are one and the same- so it is no surprise for my faith to come up very naturally in conversation.

Anjuli – it's so good to have you back! I really missed you! Regarding writing about faith, it looks like you're in a good place.

Hi Annette – I'm glad to be introduced to your blog by Shirley's guest post, and Hi Shirley – what a great book title, and all the best on your revisions!

Shirley and Annette, thanks for this thought-provoking and intellectual look at writing and talking about our faith. Like Kathy Pooler, I'm trying to weave my faith into my memoir, primarily because it has a great deal to do with my family, growing up and my relationship with my mother. Yet, I find that even though I can talk to a stranger about faith, writing about it scares me. I don't want to sound high-minded, preachy, or like an evangelist come to save the world. I suppose that has its genesis in my once shy and retiring personality as a child and teenager.

Shirley, your words have certainly helped me look on writing about my faith from a more conversation perspective. Thanks!

Ms. Shirley Showalter my name is Adam Showalter and I've been researching my familly history… I have so many questions about my mennonite past and possible future… I feel as though I need that connection to become complete.. I am hoping you may shed light onto the missing links to my familly history… My grandfather Joseph P. Showalter was a penticostal preacher before he had passed but I feel it is my calling to ensure mennonite religion lives on for future generations.. The amount of respect I hold for the mennonite and amish community is undying… please anything you can do to help would be wonderfull.. I look forward to reading your story as soon as it is published..

Hi, Adam. The Showalter name comes from my husband. He has done some family history, but he does not recall anyone with that name in the immediate line. If you live close to a Mennonite community, you might find a historical society genealogical archive in your area. There are a number of these scattered across the country. I wish you all the best in your research.

I loved what you said about showing how faith and religion has impacted you, both positively and negatively. From what I gather, you've been able to write about the negative while celebrating the positive. When I began my memoir, a Christian counselor cautioned against revealing the hurt inflicted upon me by certain Christians for deciding to divorce my husband. What I want to show is the difference between certain "religionism" and faith.

Hi, Linda. I get the distinction between religionism and faith. True faith does not have to defend itself with walls of protection and denial of the bad and ugly. It needs confession and sometimes forgiveness and always light. There is a way to tell the truth without attacking and blaming and seeking revenge. Readers can tell when a story has been covered up or aired too soon. I'm sure you can tell yours without falling into either trap. Thanks for the comment.