|

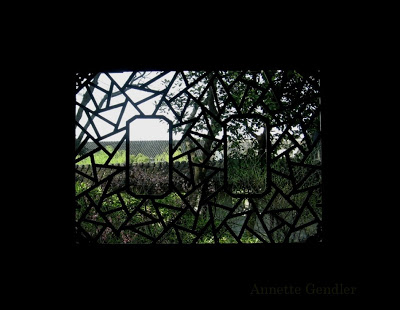

| Walkway along the canal outside of the Garden, as seen from The Fish Watching Spot |

For a long time I have been meaning to share pictures from my visit to this classical Chinese garden in Suzhou.

I hesitated because I felt I did not know enough about Chinese gardens to write about them. Now, as the landscape turns grey here in Chicago, I find myself thinking again about these gardens I visited back in late March, when the landscape there was similarly muted, and nature had not yet awoken to full bloom. So I’ve decided it is time to share, even though I still don’t know enough. Nevertheless I hope this photo essay will give you a glimpse, and ideally transport you, just a little bit, to this rather serene world amidst the bustling city of Suzhou. About a two hour drive west of Shanghai, Suzhou is a “smaller” city by Chinese standards, which means it has a metropolitan area of about 10 million inhabitants that makes it larger than Chicago.

The Cang Lang Ting Garden was originally built in the 11th century by the poet Su Shunqin, who took its name from a line in the “Fishermen” poems by Chu Ci (340 – 278 BCE): “If the water of the Cang Lang river is clean, I wash the ribbons of my official hat in it; if it is dirty, I wash my feet.”

How appropriate then, that a visitor today will still find a boat moored by the outer wall of the garden. The old and formerly walled city of Suzhou, a giant square framed by a canal, today lies in the center of a vast carpet of industrial parks and mid-rise apartment developments. It’s a city of canals (see my Tiger Hill photo essay). While most classical Chinese gardens will feature a body of water in their middle, the Cang Lang Ting is known for “borrowing” this canal that runs along its southern side.

The perimeter wall features not only an outside walkway, but latticed windows that let the visitor look in and out, thus blurring the border of the garden and making it feel much larger than it is.

A classical Chinese garden is divided into different sections, often including outdoor rooms or pavilions, none of which are arranged symmetrically. You never get a grand vista. Rather, you are led around corners, along hallways, ending in windows that frame a carefully arranged planting beyond their intricate lattice work.

While classical Chinese gardens were built rather than planted, their space arrangements do not follow the symmetry we generally expect from buildings. Notice that none of the windows in this hallway feature the same pattern. You will look in vain for any kind of symmetry in the West European sense. Rather, symmetry is to be found in balancing the four seasons, or making sure the elements (water, flora and fauna) are represented. While Chinese buildings generally favor symmetry in the sense of one side balancing the other, using a rather simple pattern, a garden was seen more like a painting; its beauty does not come from a carefully designed symmetry, but rather a “perfect” depiction of nature.

Coming around a bend, you might happen upon a little wonder, such as this window in the shape of gourd. It is one of four windows representing the seasons. Looking through, your gaze rests upon a grove of bamboo.

Then you turn another corner and you find yourself on this walkway (notice the elaborate stone pattern of the pavement) that seems to spring forward like a brook, jumping through the moon gate and on to another part of the garden, the surprise of which we cannot see yet from this vantage point.

All these walls partition the grounds in such a way that a grand illusion of space is created, while the actual garden encompasses roughly four acres in a rather rectangular parcel. Indeed, after touring this garden and another one (which I hope to share soon), I felt like I had walked a lot, which I had, and seen a lot, which I had, since every corner offers a unique design. I was genuinely tired, and my head was full of all that beauty.

Garden rooms, such as this Smelling Prunus Mume Pavilion (named after the Chinese plum tree), offer a spot to rest, receive visitors, be outside and enjoy nature while being sheltered from the summer heat and somewhat, perhaps, from the winter cold.

Looking out from the pavilion’s other side, a window imitating shattered glass again provides a frame for nature.

The idea of the Chinese garden is to bring nature to the city by, for instance, constructing a mountain out of rockery, such as this mountain in the middle of the Cang Lang Ting garden that leads up, via many “climbing paths,” to a look-out pavilion.

You've got quite an eye, Annette. Thanks for sharing.

Jennifer – thanks, glad you enjoyed it.

It looks like a lovely place!

William – indeed it was!