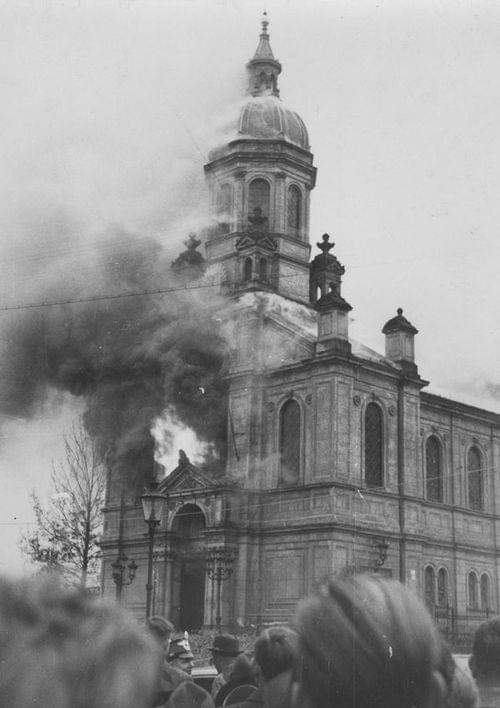

The destruction of the synagogue in Reichenberg (Liberec), November 9-10, 1938

Last year I wrote about Remembering Kristallnacht in Liberec, which is featured in my book Jumping Over Shadows. I didn’t want today’s 80th anniversary of the Kristallnacht pogrom go by without honoring it. Especially since I’ve made a new friend, thanks to my book, who grew up Jewish in Liberec (formerly Reichenberg), and who kindly forwarded me the above image.

I also feel that, in light of the recent shocking attack on a synagogue in Pittsburgh, when a white supremacist murdered eleven Jews and wounded several more during Shabbat services, a commemoration of Kristallnacht is particularly apt. Sadly, the events of Pittsburgh have shown that, 80 years after Kristallnacht, Jew-hatred is perhaps rare, at least in the U.S., but it is still alive and well, and deadly.

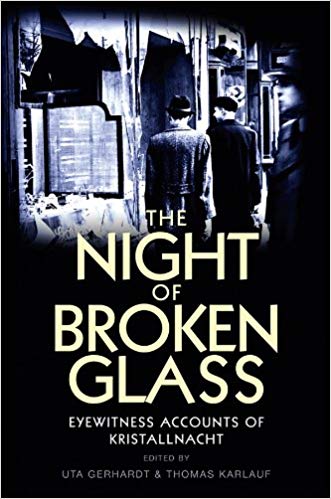

Thus my nose has been buried in The Night of Broken Glass, a collection of eyewitness accounts of Kristallnacht that my husband recently stumbled upon. Of course I’ve read plenty about Kristallnacht before, but I don’t recall ever reading eyewitness accounts. This is one of those books about something that you thought you knew lots about, until you read it and find that you didn’t.

Eyewitness accounts have an entirely different feel than anything written in hindsight.

Recorded in 1939 or 1940, these personal experiences by eyewitnesses don’t portray Kristallnacht as the opening round to the Holocaust. Rather, these people experienced Kristallnacht as the end of life as they knew it. Mainly city dwellers of decent means, they were beaten and degraded. Their property was destroyed, often in front of their eyes. One old lady was forced to smash her prized possessions with a hammer. Most men were carted off to concentration camps and only released if they could produce exit visas. Many report of community members who took their own lives.

Kristallnacht was a pogrom organized by the government, not the people.

These eyewitness accounts affirm that the Kristallnacht pogrom was an organized effort by the local SA (Sturmabteilung = storm troopers) and police, with direction from the upper echelons of the Nazi regime, Hitler and Goebbels. It was not, as the German press (all Nazi organs) later reported, initiated by a furious population. (For example, see article in the Liberec newspaper Die Zeit: “The population protested the Jewish assassination.” referring to the pretext for the pogrom, namely the murder of the Nazi diplomat Ernst vom Rath by Herschel Grynszpan, a Polish Jew living in Paris.) The nighttime attacks on Jewish homes (all happening after midnight) were well planned in advance. Each SA group had a designated area to “sweep.” The assassination in Paris had simply been the pretext they had been waiting for.

The story of this book is itself an adventure.

It began as a writing contest initiated by Harvard academics and advertised in the New York Times on August 7, 1939 as “Prize for Nazi Stories: Harvard Faculty Men Seek Personal Histories of Experiences.” Submission deadline was April 1, 1940. More than 250 people from all over the world sent in their stories. Submissions came from the U.S., England, Palestine, and far off Shanghai (which, incidentally, was the only place that admitted Jews fleeing Europe without a visa – see my story on the Shanghai Jewish Ghetto). For many emigrants, the contest’s first prize of $500 would have secured survival for a family for several months. Many entrants described winning the contest as their last hope.

Sadly, World War II overtook the project.

After the prizes were awarded (the introduction gives no details on this), its main chaperone, Harvard sociologist Edward Hartshorne, put together a manuscript of what he considered the most impressive accounts. Titled “Nazi Madness,” he hoped it would draw attention to what was happening to the Jews in Europe. He offered the manuscript to a publisher in August 1941. However, when he himself joined the U.S. Secret Service in September 1941, the project lost its engine. After Hartshorne was assassinated in Germany in 1946, the project fell into oblivion.

It wasn’t until the 1990s that his biographer Uta Gerhardt traced the manuscript to Berkeley. She and Thomas Karlauf edited what we have now in The Night of Broken Glass. It is, as Karlauf writes in his introduction, a stunning, chilling, and totally engaging collection of reports that “document the end before the end.” (p. 30) Which is why my nose has been buried in it.

Life before the end before the end

To wrap this up on a less somber note, and also to convey a bit what life was like before the end before the end, I’m sharing the below film. It captures street life in Liberec before World War II. My new acquaintance from Liberec brought it to my attention. What an eerie treasure to see my grandparents and my dad’s former everyday world in motion! A few times the camera pans over the cityscape. Unfortunately, the images are too blurry for me to ascertain whether the tower of the synagogue still graced the skyline, or whether it had already been obliterated when this film was taken.

Ještě jednou minulost, odpočinková…

Posted by Jarda Vojtěch on Friday, November 6, 2015

Sounds like a sad, but riveting book.

Yes, sad but also these eyewitnesses got out so it’s easier to stomach. It’s just fascinating to read these accounts that were written right after Kristallnacht and before things really descended into hell.

Thank you for pointing out the book. I noted the anniversary mentioned in another blog today, with the haunting waterside memorial to the holocaust in Budapest.

Yes, the riverside Holocaust memorial in Budapest is truly stunning. Something I’d like to see for myself someday soon.