This low stone wall marks the circumference of the barn in Jedwabne, where more than 300 Jews were burned to death in July 1941.

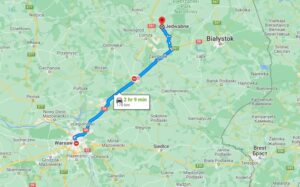

After our visit to the Warsaw Jewish Cemetery, the first stop on our tour of Holocaust sites in Poland was the little town of Jedwabne, a shtetl in the northeast of Poland. In this town, in 1941, at least half the population had been Jewish for centuries.

Nevertheless, on July 10, 1941, as the Germans were taking over northeastern Poland, the Polish residents of Jedwabne murdered their Jewish neighbors, principally by locking more than 300 of them in a barn and setting it on fire.

How great must your hatred of your neighbors be to force them out of their homes with axes and pitchforks, herd them into a barn and burn them alive?

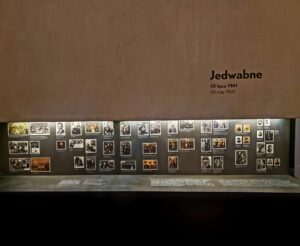

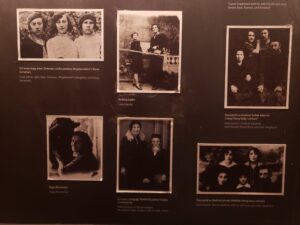

The Jedwabne exhibit at the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews (excellent museum!) in Warsaw thankfully honors some of the victims of Jedwabne.

Some of the Jewish residents of Jedwabne murdered on July 10, 1941 (POLIN Museum)

Can a town be just a town?

Can a field be just a field when under its surface there are two mass graves of people, who used to live there, brutally murdered?

Of course it can’t be when you walk around there with the knowledge of what happened there in your head. Even more so when the victims still lie in a mass grave there. It is, for all its bucolic mundanity, a sinister place.

And yet, the current residents were respectful of our group. A farmer working the field next to the memorial kindly shut off his tractor while we were there.

What, I asked myself, must it be like to live in a place like this? Where such a horrible thing happened fairly recently? Perpetrated by the forebears of many of those who still live there now?

And, moreover, where the evidence is still present in two mass graves?

The Jedwabne Massacre wasn’t talked about until 2001, when the Polish-American historian Jan Gross published his book Neighbors. The few survivor accounts were borne out by archeological finds. A subsequent documentary got massive Polish media attention, blowing up the long held view that Poland had only been a victim in WWII, not a perpetrator.

For us 21st century travelers, Jedwabne presents one piece of sobering evidence why the genocide of the Jewish people happened in this part of the world.

Were Jews shipped off to the extermination camps from other places in Europe? Yes, they were. But the extermination camps were all located in Poland.

And yet, thank God, there was an alternative:

A nearby Polish farmer family, Antonina and Aleksander Wyrzykowski, managed to hide several Jews on their farm until the end of the war in Poland (January 1945), when they themselves were driven out for having helped Jews. In 1976, they were recognized as a Righteous Among Nations by Yad Vashem.